Pituitary Tumor

What’s in this section?

Overview

A tumor of pituitary gland cells is often called a pituitary adenoma. Pituitary adenomas are the fourth most common intracranial tumor. They are almost always benign and slower growing. There are about 10,000 pituitary adenomas diagnosed each year in the United States. Pituitary adenoma patients are most often 30–50 years old. Pituitary carcinoma (cancer) can occur, but it is extremely rare.

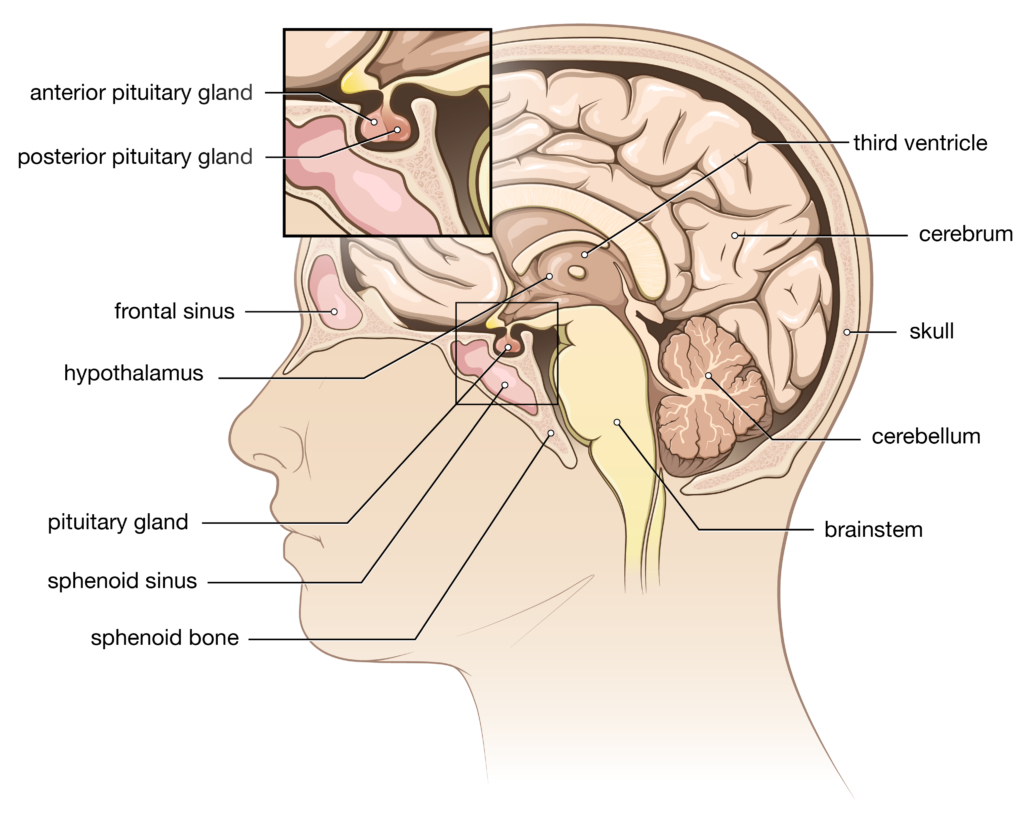

The pituitary gland is about the size of a kidney bean. It sits in a saddle-shaped cavity of bone called the sella turcica, which is located along the bottom of the skull. The pituitary gland is very much the “master control” gland which regulates many body functions, organs and other glands by releasing its pituitary hormones into the bloodstream. Hormones are substances that regulate the work of glands and organs. Hormone imbalance can lead to a wide variety of symptoms affecting general well-being and sexual function.

The pituitary gland is divided into two parts. The anterior (front-side) pituitary produces most of the signaling hormones. It accounts for about 80% of the gland. Most adenomas arise from this part. The posterior (back-side) pituitary is an extension of an area of the brain called the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus produces two hormones (oxytocin and vasopressin) which are transported down the pituitary stalk (a tube of nerve endings called the infundibulum) where they are stored in the posterior pituitary for later release. Adenomas rarely occur in the posterior part of the gland.

Pituitary adenomas are classified as functioning (hormone producing) or non-functioning (no hormone activity). Most adenomas remain within the confines of the sella turcica. However, some may grow into the bone or beyond the sella turcica and affect the nerves, blood vessels or sinuses in the area.

Microadenomas are one centimeter (4/10 inch) or less in size and often secrete anterior pituitary hormones. Nearly half are even smaller in size. Microadenomas are usually discovered because of the effect of their overproduction of hormones. Some may be too small or not produce enough hormones to be detected.

Macroadenomas are larger than one centimeter and usually are non-functioning. They are typically discovered because they press on other structures (especially those involving vision), produce headache or compress and compromise the function of the normal gland.

Pituitary apoplexy is a rare condition. It is considered to be an endocrine emergency. It is the name given to sudden infarction (tissue death due to loss of blood supply) or hemorrhage into the pituitary gland. Often, it is felt to be tied to the presence of an underlying pituitary adenoma.

Signs and Symptoms

The signs and symptoms associated with a pituitary adenoma depend on its size (microadenoma vs. macrodenoma) and if it is a functioning or non-functioning tumor. The symptoms associated with functioning adenomas are tied to the hormone they secrete in excess. Rarely, a pituitary tumor may produce more than one hormone.

- Prolactinoma This tumor secretes prolactin. It is the most common functioning adenoma. Prolactin normally is involved with the growth and development of female breast tissue and the production of milk following the birth of a baby. Excessive prolactin secretion by the tumor can produce infertility, bone weakness (osteoporosis) and decreased libido (interest in sex). In females, it can decrease estrogen, delay or stop menstrual periods before menopause and produce galactorrhea (an inappropriate discharge of a milk-like secretion from the breast). In men, it can decrease testosterone and facial and body hair, produce gynecomastia (increased amount of breast gland tissue) and cause erectile dysfunction.

- Growth hormone (GH)-secreting adenoma This tumor secretes somatotropin (growth hormone) which regulates physical body growth and metabolism. It accounts for 20% of all functioning adenomas. In childhood, it results in gigantism and in adults, excessive GH causes acromegaly.

- Adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH)-secreting adenoma ACTH regulates the adrenal gland to produce and release hormones such as cortisol and aldosterone. These hormones govern the metabolism of carbohydrates and protein as well as salt and water balance. The overproduction of cortisol by the ACTH-secreting pituitary tumor results in Cushing’s disease.

- Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH)-secreting adenoma TSH stimulates the release of hormones made by the thyroid gland. These control your baseline rate of metabolism. Thyroid hormones affect almost every organ in your body. Excess production can lead to problems such as a speedy or irregular heart rate, weight loss, protruding eyes, tremors, and increased appetite, sweating or warmth. TSH-secreting adenomas are very rare.

- Gonadotropin-secreting adenoma These pituitary tumors secrete luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicular stimulating hormone (FSH). These hormones play an important role in sexual development and the regulation of ovulation (and menstruation) and sperm production by controlling the production and release of other sex hormones (estrogen and testosterone). These tumors are not common.

- Null cell adenoma These are non-functioning pituitary adenomas. They account for about one-third of cases. They are often macroadenomas when discovered.

Potential Causes

There are no known environmental or lifestyle risk factors for developing a pituitary adenoma. The few known risk factors are generally related to genetic issues. Pituitary tumors are associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) types I and IV, McCune-Albright syndrome and Carney complex.

Diagnosis

The development of symptoms often leads to a physician visit. Diagnosis of a pituitary adenoma starts with a medical history and physical examination including a vision assessment. Blood and urine hormone tests will be obtained as indicated. Magnetic resonance imaging MRI is the preferred imaging test and computerized tomography CT may be used if the patient cannot undergo an MRI.

Treatment Options

A customized treatment plan is put together for you based on:

- The tumor’s type (functioning or nonfunctioning) and size (micro or macroadenoma)

- Your age and general health

- Your tolerance for certain treatments

- Your preferences

Treatment for a pituitary tumor may include one or a combination of the following options:

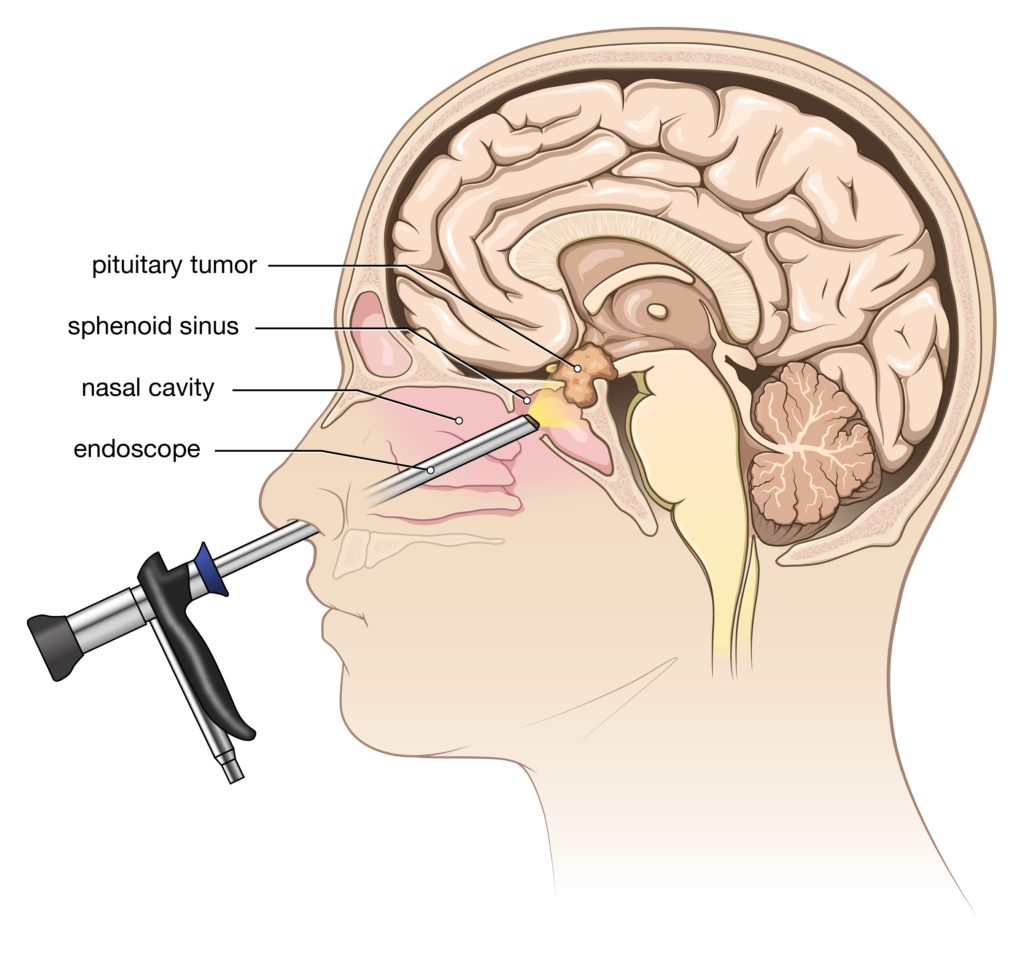

- Surgery Surgery is usually the first consideration if treatment is needed, except in the case of a prolactinoma. In most cases, the surgery for a pituitary adenoma is performed through a minimally invasive “transsphenoidal” skull base approach. Access to the tumor occurs through the sphenoid air sinus behind the nasal cavity.

- Endoscopic skull base surgery This surgery is done through the nostrils, with your neurosurgeon working together with an ENT surgeon. No incisions are made in the skin. Computerized image guidance or intra-operative x-ray imaging is often used to assist with surgical accuracy. A long, thin micro-camera is inserted into one nostril. The sphenoid sinus behind the nose is entered, providing access to the bony sella turcica (where the pituitary gland is located). An opening is made through the floor of the sella. After the tumor is removed, the opening can be sealed shut in a variety of ways. A temporary spinal fluid drain in the lower back or packing of the nostrils may be used to promote healing of the seal. Usually, you will be in the hospital for only a few days.

- Open skull base surgery This transsphenoidal procedure is quite similar to the endoscopic version, except that a high powered microscope is used in place of the micro-camera. An incision may be made at the top of the gumline or in the nostril.

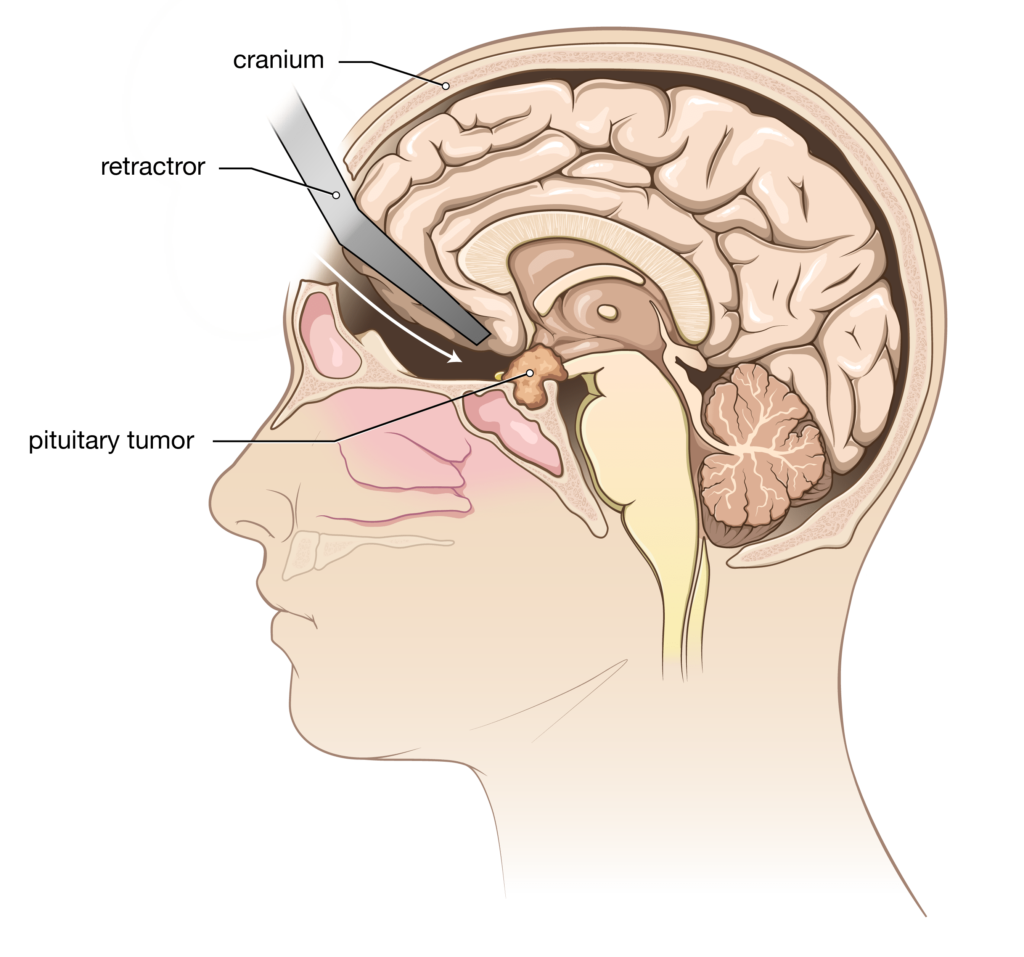

- Open craniotomy This approach is used if the tumor has grown far above the sella turcica and your neurosurgeon feels that transsphenoidal removal would be too risky or less successful. Following a skin incision, a window of bone in the skull is removed (and replaced at the end of the operation). A high-powered microscope is used to visualize and remove the tumor. You will need to stay in the hospital for a few days after surgery, with the length of stay determined by the extent of surgery. Typically, you will undergo a brain MRI scan on the day following your surgery.

- Radiation therapy Generally, radiation is not the first form of treatment. It is usually reserved for tumors which recur or could not be completely removed. It can be effective in stopping further growth of the pituitary tumor and, in some instances, can even lead to shrinkage. Radiation therapy may take up to a year to work. Options include standard external beam treatment, stereotactic radiosurgery and proton beam therapy.

- Medications The medical management of pituitary tumors is dependent upon the exact type of hormone the tumor is producing.

- Prolactinoma Medical treatment is effective and is usually the first consideration for a prolactinoma. Prolactin levels return to normal and there usually is some shrinkage of tumor along with improvement in symptoms. The medications are called dopamine agonists. Cabergoline (Dostinex®) is now used more commonly than bromocriptine (Parlodel®). Surgery is considered if there are intolerable side effects, a poor response to medical treatment after six months or there is a desire to become pregnant. These dopamine agonists may also be used as second- or third-line treatments for some of the other pituitary adenomas.

- Growth hormone-secreting tumor Surgery is generally the first line of treatment. If needed, a man-made version of somatostatin (a hormone that hinders or blocks the effect of growth hormone) or an agent that blocks growth hormone receptors may be administered.

- ACTH-secreting tumor Surgery is the first line of treatment for Cushing’s disease. If needed, cyproheptadine (Periactin®) can suppress the production of ACTH in some tumors. Other medications are available to block the adrenal gland from making cortisol or block cortisol receptors in the body. Surgical removal of both adrenal glands may also be a consideration for persistent severe Cushing’s disease.

- DDAVP (desmopressin) This is a synthetic version of ADH (antidiuretic hormone or vasopressin). It is used to treat diabetes insipidus (DI) which results from lost production of ADH. Without ADH, the kidneys are unable to prevent the unregulated loss of water which results in extreme thirst, excessive urination and electrolyte imbalance. Mild DI can be managed by drinking enough fluid to maintain an appropriate balance of water and electrolytes.

Follow-up care includes regular monitoring for the effectiveness of treatment. In the case of a functional adenoma, hormone levels can be monitored. MRI scans may be obtained. Following surgery or radiation therapy, some hormones may need to be replaced. It is not unusual to need short-term treatment with DDAVP and, at times, long-term therapy may be required. A variety of physicians may be involved in treatment including your neurosurgeon, endocrinologist, ENT physician and possibly radiation oncologist.

Conditions

Request an appointment online and we will guide you through the next steps

Get to know the physicians of Goodman Campbell

Goodman Campbell

Patient Stories

Request an appointment online and we will guide you through the next steps.